AI Sovereignty: The Emperor Has No Clothes

Most countries should stop chasing illusions of AI sovereignty and focus on building and strengthening talent pipelines.

There isn't a week that passes where I'm not hearing a discussion about AI sovereignty. While this topic has been circulating for some time, it has recently become perhaps the dominant theme in many AI conversations. I've always felt somewhat out of place in these discussions because it has seemed obvious to me that, with very few exceptions like the US or China, no country possesses AI sovereignty, nor that there is any realistic path to achieving it.

Initially, I wondered if I was missing something fundamental. But increasingly, I feel like the child in "The Emperor's New Clothes."

At a recent talk I gave at the Swiss Software Festival, this was one of the key discussion points. I argued that for Switzerland (and I believe this holds true for virtually every country except the United States and possibly China), AI sovereignty doesn't exist. It's a pipe dream, an illusion. But it remains incredibly appealing, and its temptation might actually prevent us from focusing on more realistic goals.

Let me explain why I think this is the case, and what we should focus on instead.

Defining Sovereignty in the AI Context

To have sovereignty means possessing decision-making power and the agility to act independently. You essentially control your own destiny. A nation with AI sovereignty would be able to make decisions about AI development and deployment without external constraints, fully independently.

For true AI sovereignty, a nation would need:

Substantial computing power under its direct control

Independent and substantial compute infrastructure, i.e. compute that isn't restricted / restrictable by other nations

Extensive data resources for training and development

Deep talent pools of engineers and researchers

Autonomous regulatory frameworks free from external pressure

Energy independence to power these systems without relying on others who could potentially restrict access

My contention is straightforward: outside of the United States and possibly China, no nation currently meets all these criteria.

A Reality Check from Switzerland

Consider my own country, Switzerland. We satisfy exactly one of these requirements: we have talent. That's where any aspirations for AI sovereignty would end.

We don't manufacture chips. We're a small, privacy-conscious nation with limited data resources. We lack energy independence. Even our regulatory autonomy is limited; we can of course create Swiss regulations, but we are still heavily shaped by EU rules, despite not having a say in their formation.

Given these realities, discussions on how Switzerland might achieve AI sovereignty strike me as fundamentally illusionary.

These aren't challenges that can be overcome simply through political will or financial investment. Developing cutting-edge semiconductor manufacturing is an enormously complex undertaking that requires decades of expertise and infrastructure development. Data availability reflects deeply rooted cultural and legal frameworks around privacy. Energy independence would require massive investments in both nuclear and renewable sources, particularly challenging for a small, landlocked country in the heart of Europe.

The Fundamental Question: Is AI Sovereignty Even Desirable?

This raises a more fundamental question: would it even make strategic sense for most countries to pursue AI sovereignty?

I would argue that for most nations, the answer is no. They are simply too small.

The European Union, with its 450 million people, could theoretically achieve the scale necessary for AI sovereignty. The bloc has the potential to match or exceed U.S. capabilities. Yet even here, decisive action is lacking, which is, frankly, incredibly disappointing. I am not talking about occasional local efforts, or even ambition, all of which is great. I’m talking about the kind of “go big or go home” approach in action that would be needed if one were serious about AI sovereignty.

Embracing Talent Sovereignty

My point of view that I shared at the Swiss Software Festival is this: accepting that AI sovereignty is unrealistic for most countries doesn't mean abandoning the AI revolution at all.

AI presents enormous opportunities. Yes, we must acknowledge our dependencies on other nations in this domain. But interdependence is a fundamental characteristic of our globalized world. Most countries have critical dependencies on others, and this interconnectedness has, by and large, contributed to global stability and prosperity over recent decades.

What can most countries do immediately and effectively? Focus on what I would call talent sovereignty.

A robust pipeline of technical talent, i.e. professionals who can leverage AI advances and build innovative solutions and applications for their domains, represents one of the most powerful levers available to nations. This is especially true when your talent is so strong that it not only serves local needs but also attracts international collaborators, investment, and opportunities to your country.

Why Talent Sovereignty Matters

Talent is central for a number of reasons.

Rapid adoption and innovation: With talent, you can quickly integrate leading AI technologies and build world-class products and services on top of existing platforms. Yes, selling GPUs is great business, but most wealth generation in AI in the long run will be in applications.

Localization and adaptation: Don’t like a limited offer of US and Chinese AI? Take global AI developments and adapt them to local contexts, values, and regulatory requirements. The Swiss LLM initiative exemplifies this approach, and is precisely the kind of targeted, strategic initiatives that make sense. Needless to say, this needs strong talent.

Knowledge transfer: Talent is needed anywhere in an economy. If you get out of the way of talent, it will accelerate the integration of AI innovations into industry and the broader economy, creating widespread benefits.

Education and research investment: Because talent is so central, your first task is in ensuring you maintain and expand talent pipelines through sustained investment in education and research infrastructure.

The Overlooked Talent Crisis

What surprises me as much as the unrealistic pursuit of AI sovereignty is how little attention is paid to developing talent pipelines.

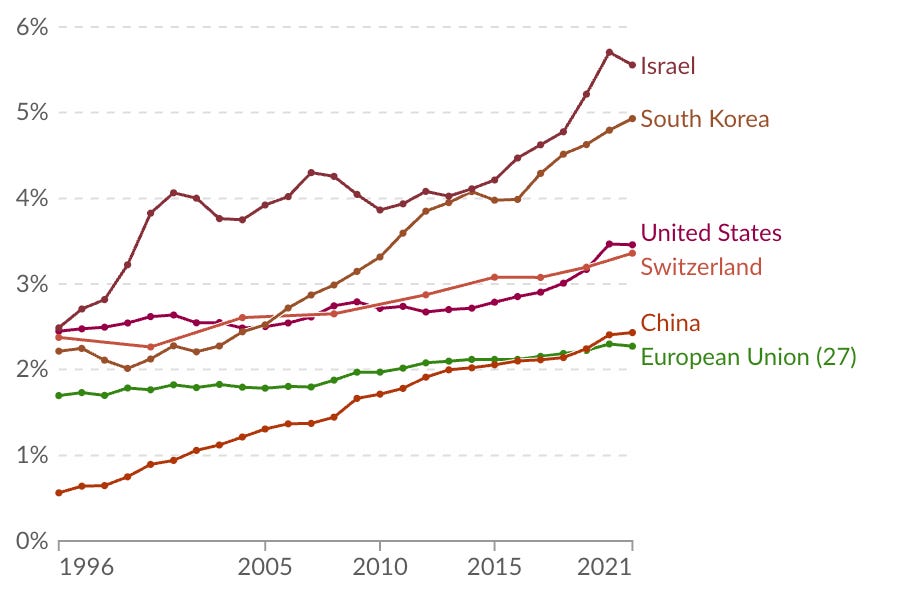

Switzerland has done reasonably well in this regard, though recent discussions about budget cuts in education and research are deeply concerning and counterproductive as we enter the AI age. And while Europe more broadly has some world-class research universities, many countries still invest disappointingly little in R&D and higher education, especially in technical fields.

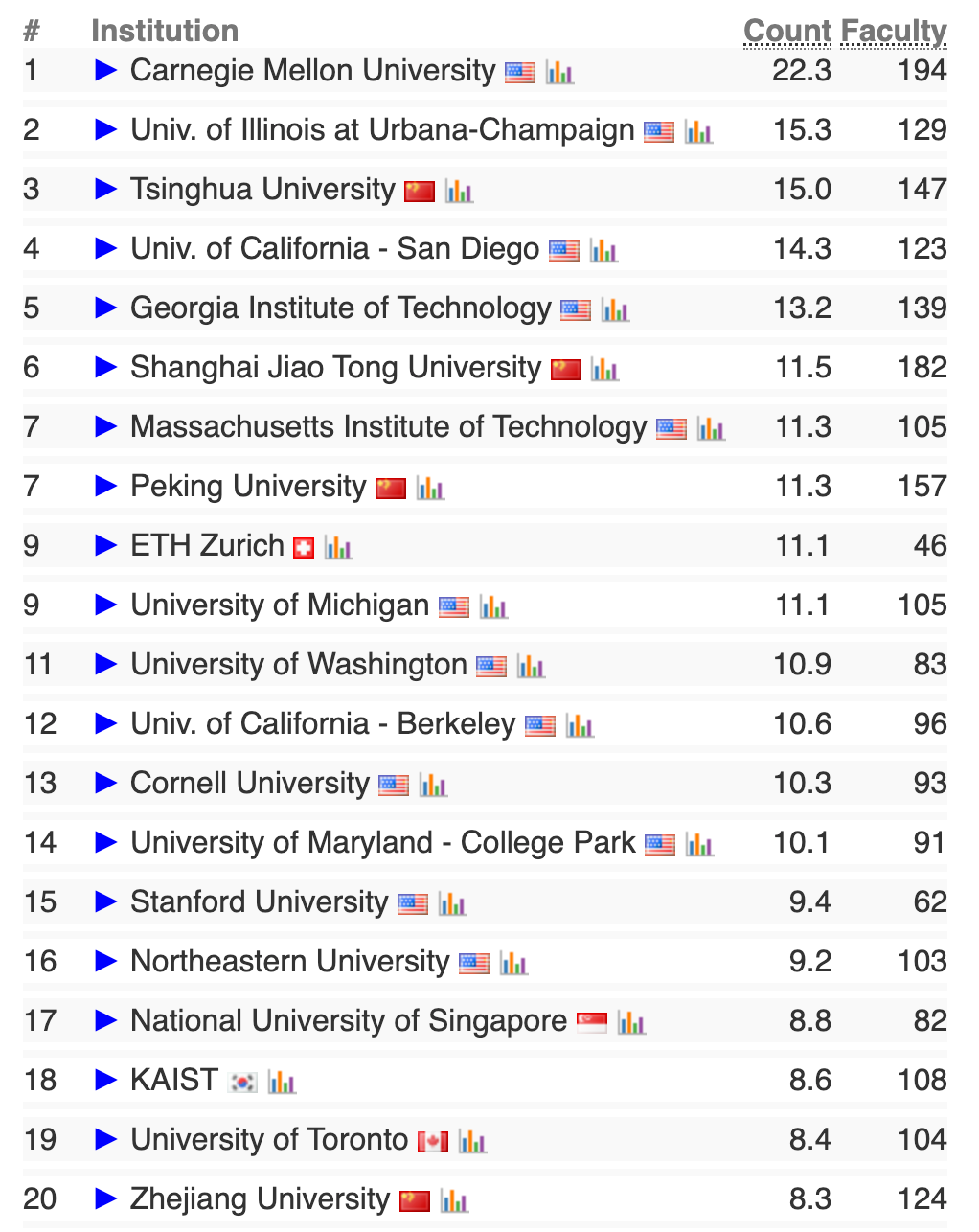

The concentration of leading universities in the United States is striking. CSranking.org provides a useful metric for evaluating technical schools based on their 2015-2025 performance. While not all technology is computer science, and talent means more than conference publications, it nevertheless offers a relatively objective measure for assessing talent production (as opposed to softer metrics like reputation or institutionally meaningless indicators like certain medals). The rankings tell a sobering story: the top tier is dominated by U.S. institutions, with no EU university appearing in the top 20.

This is particularly striking given Europe's historical position as a center of scientific advancement. While some lag following World War II was perhaps inevitable, the failure to regain leadership in the subsequent decades is a major missed opportunity, to put it as diplomatically as possible.

This puzzles me to no end. It should be obvious that these outcomes aren’t a reflection of some sort of local intelligence or a lack of hard work. They’re the result of opportunities created by government investment, especially in the early stages (private investment certainly plays a role, but historically, it tends to follow where public funding leads).

Moving Forward

The path forward is clear, in my view: if small to mid-sized nations want to position themselves strategically in the AI era, they should prioritize talent sovereignty. Rather than chasing the illusion of complete AI independence, focus on building and maintaining the human capital that can thrive in an AI-transformed world.

In the end, success in the AI age won't be determined by whether a country can produce its own chips or control its own compute infrastructure. It will be determined by whether it has the people capable of building remarkable things with the tools available to them. For that you need talent production, and thus investment in education and R&D.

CODA

This is a newsletter with two subscription types. I highly recommend to switch to the paid version. While all content will remain free, all financial support directly funds EPFL AI Center-related activities.

To stay in touch, here are other ways to find me:

Completely agree, Marcel. I spent yesterday with a customer having similar debates. We burned an hour on “AI sovereignty” hypotheticals - what if the US pulls the plug tomorrow - while the actual work stood still. If you want frontier models today, your options boil down to the two hyperscalers willing to give you the security and privacy guarantees your vertical/data needs. Switzerland is not spinning up Opus-class capacity any time soon, and waiting for that fantasy just keeps the use cases on the shelf.

Well written thoughts, dear Marcel - a good contribution to the discussion: Thanks!