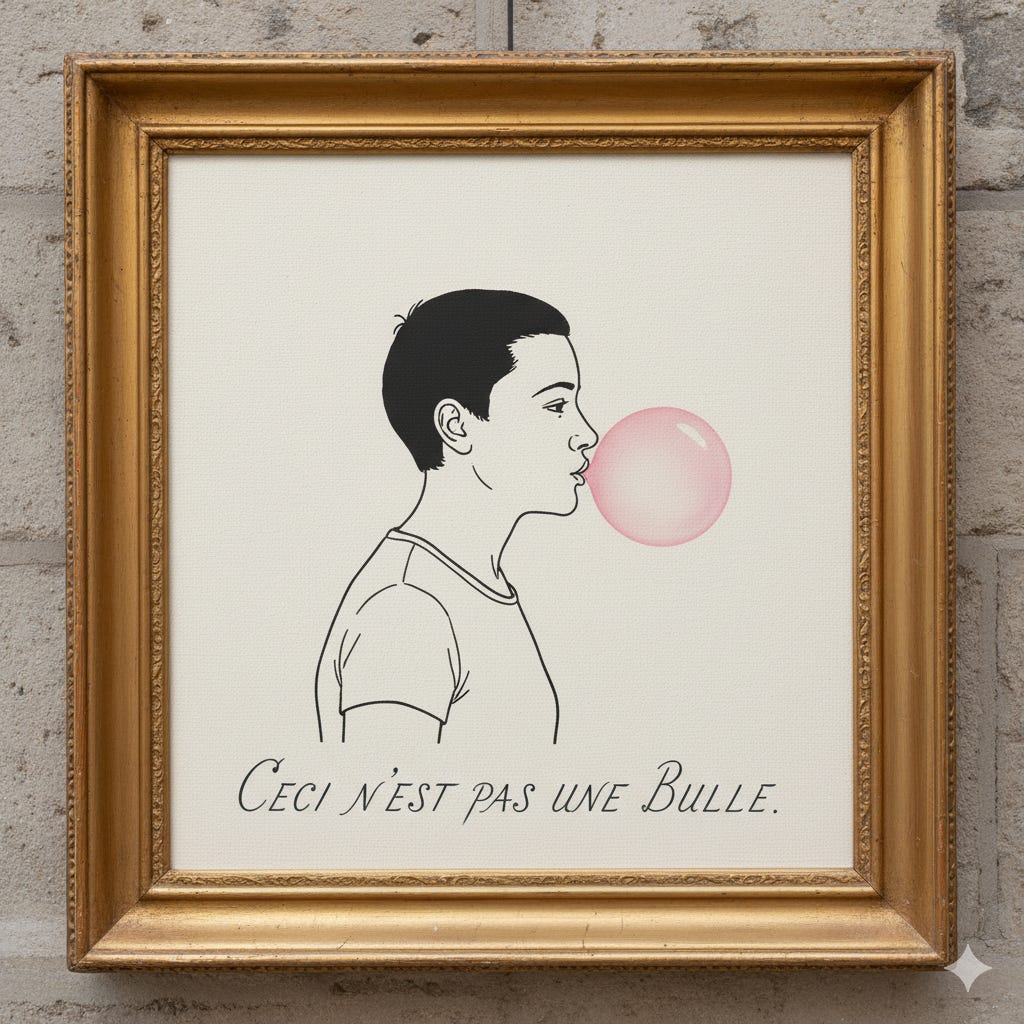

Overcapacity + Weak Demand = Bubble. AI is not yet a Bubble.

Don't judge a bubble by its looks. Instead, look at the underlying dynamics of capacity and demand.

Everyone wants to know if we’re in an AI bubble. In this post, I’ll give you the definitive answer.

Of course not. But many posts today sound just like that. They latch onto superficial similarities with past bubbles, suggesting, “Look, we had a bubble before; let’s list ways this looks similar!” However, comparing current events to past bubbles, without looking carefully at underlying dynamics, isn’t very helpful. It’s akin to comparing every accident to an explosion. The crucial question we should ask is whether current dynamics actually risk causing a crash.

Take, for example, comparisons to the railroad bubble. You could spend weeks reading about this historical event, but fundamentally, its underlying issue was weak demand paired with major overcapacity, an imbalance that inevitably led to collapse. The dot-com bubble followed a similar pattern: overinvestment driven by unrealistic expectations of rapidly materializing demand. Both cases ultimately saw demand materialize, but far slower than anticipated.

Today’s AI situation is fundamentally different. We have compute undercapacity and overwhelming demand. Let me emphasize this: many companies struggle profoundly to access sufficient computing resources to meet demand. That’s not a bubble, it’s quite literally the opposite! It’s exactly why massive investments continue to flow and stock prices keep rising. Therefore, calling today’s AI market a bubble is misguided, as the essential bubble components - overcapacity and weak demand - simply aren’t present.

So, nothing to worry about?

Right now, no. But tomorrow could be a different story. Let’s examine the two key factors again: overcapacity and weak demand. Since the concept of overcapacity relates to demand, the two are essentially two sides of the same coin. So let’s simplify by focusing solely on demand.

It’s safe to say the demand for AI is very strong, and it’s difficult to imagine a future in which this demand doesn’t continue to grow. AI is incredibly useful and will only become more useful, which naturally fuels increasing demand. Some argue it’s all a mirage, claiming AI isn’t genuinely useful, but study after study and survey after survey consistently show the opposite: people find AI immensely valuable. Of course, there’s overselling and some overestimation of what current models can achieve. Yet, at the end of the day, users experience firsthand the real capabilities of today’s models, reinforcing ongoing demand. Given the clear evidence that AI capabilities will keep improving, we can confidently predict demand will also rise.

One might conclude, therefore, that as long as demand continues upward, current compute investments are entirely sensible. In other words, we’re not witnessing overcapacity but a normal, justified build-out to satisfy this growing demand. This reasoning is precisely why I find it hard to argue today that we’re in an AI bubble. The rapid growth might seem confusing, but it doesn’t indicate a bubble - it simply reflects strong, healthy expansion driven by an extremely useful technology.

Demand of what?

But here lies the crux. People want AI, which means they demand AI services, not compute hardware itself. Currently, there’s a tight link between compute hardware (GPU infrastructure, essentially) and AI because present-day models require enormous computational resources. But what if this connection weakens? Such a scenario could indeed create conditions for an AI bubble.

Imagine, hypothetically, inventing an AI architecture that delivers top-tier AI model performance using just 1% of current compute needs. The demand for AI would remain strong - possibly even increasing due to reduced costs (the famous “Jevons Paradox”) - but not enough to utilize fully the vast GPU parks built at great expense. Suddenly, 99% of that infrastructure would become redundant overnight, despite continued high demand for AI itself. You simply can’t scale demand fast enough to justify such surplus infrastructure. You cannot “jevons” your way out of this.

And this is where the condition for a bubble - not enough demand for the overcapacity of compute - would be met.

Is this realistic?

How realistic are such massive compute efficiency increases? A 100x efficiency gain may seem crazy. But consider this: we still don’t fully understand why these models work so well. We “grow” them and can see that they work, but not exactly why. Yes, we understand scaling laws and some circuit-level behaviors, but we are still growing systems rather than engineering them from first principles. Which means there is probably massive room for architectural innovation.

And the evidence for radical efficiency gains is already appearing. Take Giotto.ai. In an episode of the Inside AI podcast (of the EPFL AI Center), CEO Aldo Podestà explains how their model with just 200 million parameters (with an m, not a b) is currently a top contender at the ARC-AGI 2 leaderboard. That is a hint that the right architectural choices might be orders of magnitude more efficient. Of course, these models won’t have the internet “memorized” like modern LLMs. But that might simply not be necessary.

To make that point, Andrej Karpathy, OpenAI co-founder, has suggested that the “cognitive core” of AGI could run on a billion parameters, though he thinks that is still 20 years away. And then there is Nature’s proof of concept: the human brain reaches general intelligence on roughly 20 watts. Clearly, things can be done much more efficiently.

This might not happen overnight. If we see 10x efficiency improvements year after year, current compute investments could remain reasonable, or slowly obsolete gradually over three to five years (which is their expected lifetime anyways). It might still be a deflating bubble, just a slower one. At this point, it might not even be a bubble, just a regular growth cycle.

The question is not whether more efficient approaches exist. They clearly do. The question is when someone figures them out, and whether they are 2x, 10x, or 100x at once.

One more thing

I have a book out! Readers of this substack might know that I’ve been working on a general-audience book about AI. I’m delighted to announce that the French version is now available, and the German version will follow in mid-November. I’m currently working on the English translation, though I’ll first need to find an English publisher. In any case, if you speak French or German, do have a look. I’m sure you’ll enjoy it!

One other thing

You probably also know that I’m the organizer of a large applied machine learning event called AMLD. For its 10th edition, we’ve renamed it the AMLD Intelligence Summit. It will take place from February 10th to 12th, 2026, on the EPFL campus, and the program will be absolutely fantastic. You definitely don’t want to miss it. As you might imagine, proximity to a technology school ensures a very low tolerance for hype or nonsense, making it a high-signal, low-noise AI event. Early bird tickets are now available for a limited time, and I highly recommend securing yours soon, as they’re substantially cheaper than the upcoming full ticket prices.

CODA

This is a newsletter with two subscription types. I highly recommend to switch to the paid version. While all content will remain free, all financial support directly funds EPFL AI Center-related activities.

To stay in touch, here are other ways to find me:

The architectural efficiency risk you outlined is the most underappreciated threat to current AI valuations because a sudden 10x or 100x improvement would strand billions in infrastructure investment overnight. The Giotto.ai example is particulary compelling since 200M parameters competing on ARC-AGI leaderboard suggests we might be grossly overbuilding for the eventual cognitive core requirements. Your point about not being able to Jevons your way out of overcapacity is brilliant because even if demand doubles or triples from lower costs, you still can't absorb 99% redundant capacity fast enough. The comparison to railroad and dotcom bubbles is apt, but the key difference you identified is that in those cases demand materialized slowly, whereas here the risk is that demand stays strong but the substrate underneath completely shifts.

I mostly agree but there is a counter argument I would like to make. The trillions being invested in GPUs are capex with an amortization time of 3 to 5 years. Where is the income justifying this investment going to come from? Because current services di not generate anywhere near these amounts…