The Stanford AI Jobs Paper: It's Not What You Think

It's the automation vs augmentation issue - again.

A Stanford paper came out last week, seemingly showing AI is killing jobs for young people. Not surprisingly, the world freaked out. "Software developers down 20%!" "Entry-level apocalypse!" "Gen Z is doomed!"

I really like the paper. It’s well done. But still: I do think everyone's missing the real story. Talk about a canary in the coal mine… 😅

Yes, the paper shows young workers in AI-exposed fields are losing jobs. But there is an interesting aspect in the methodology that I haven’t seen much discussion about. The same field can be both dying and thriving at the same time - based on whether we look at automation with AI, or augmentation with AI.

What the Paper Actually Says

The researchers analyzed payroll data from millions of US workers. The headline findings are quite someything:

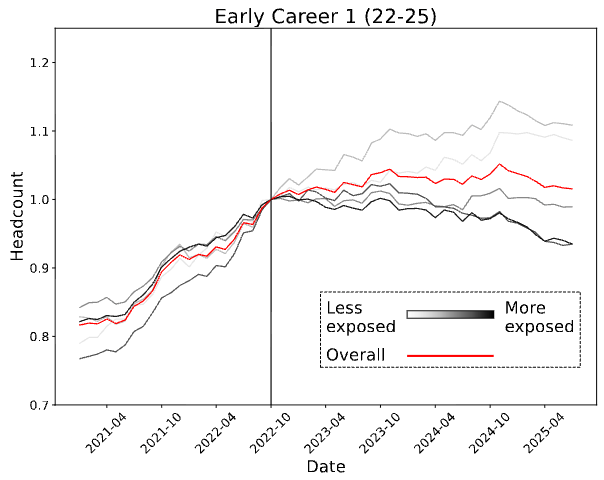

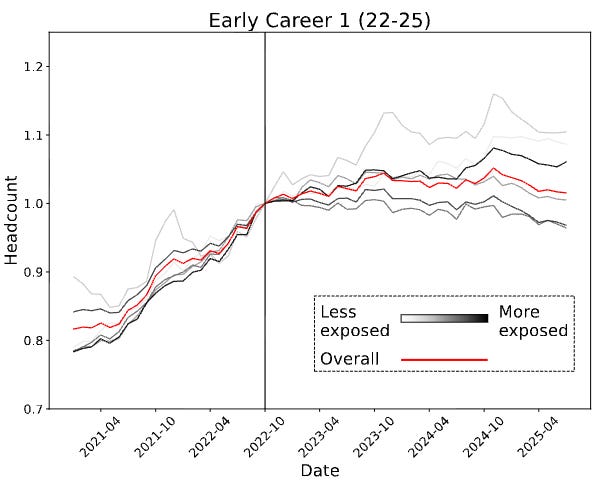

Since late 2022, 22–25 year‑olds in the most AI‑exposed jobs saw ~6% lower employment in the raw data; controlling for firm shocks, the relative decline vs. least‑exposed jobs is ~13%.

Software developers under 25 are down nearly 20%

Meanwhile, older workers in the same jobs kept growing

The paper calls these young workers "canaries in the coal mine." Fair enough. But here's where it gets interesting.

The researchers didn't just measure which jobs are exposed to AI. They used data from another study (the Anthropic Economic Index) that had analyzed millions of Claude conversations to understand how people actually use AI in different jobs. That study found two patterns:

Automative uses: AI does the work, human just delegates

"Format this documentation in Markdown"

"Fix this Python error" (followed by endless back-and-forth of error messages)

Augmentative uses: Human does the work, AI enhances it

"Review my SQL query for finding duplicate records"

"Explain how neural networks work"

The Stanford team took these automation/augmentation scores and matched them to the employment data.

Here’s where it gets interesting: When AI use is augmentative, the entry‑level declines largely do not appear, and the highest augmentation group actually grows!

The paper is quite clear about this:

Our third key fact is that not all uses of AI are associated with declines in employment. In particular, entry-level employment has declined in applications of AI that automate work, but not those that most augment it.

and

While we find employment declines for young workers in occupations where AI primarily automates work, we find employment growth in occupations in which AI use is most augmentative. These findings are consistent with automative uses of AI substituting for labor while augmentative uses do not.

(emphasis mine).

In automative patterns, you're basically just a messenger between the problem and the AI. In augmentative patterns, you own the work and use AI to level up.

Let’s think about what this means. Software development - the poster child for AI job losses - contains both patterns. Notice how two of the examples above look like software development examples, one using Python, the other SQL. Developers doing automative work don’t have a great future. But developers using AI augmentatively might be doing just fine.

The paper can't really show this because the data are occupation‑level, so within‑occupation heterogeneity is a plausible hypothesis rather than a result. But the logic is right there.

Why This Matters

I’m reminded of the debate about AI in education. Some studies warn that students are “getting stupid” with AI - recall the MIT study that made headlines as “AI destroys your brain” - while others report tremendous benefits of AI use.

The pattern is similar. If students simply let AI do the homework for them, they’re not learning (which, after all, is the point of education). No surprise there. But when AI is used as an educational augmentation, for instance in a Socratic way, guiding learners through problems, helping them work out solutions, and pushing them to engage more deeply, then the effect is usually a massive boost to learning.

It seems to be a similar story here.

Why This Matters

Are we truly surprised that tasks that are automatable, are automated? Would we expect it to be any other way? This has always been the reason for technology development: to do a certain task with less energy. If it uses less energy, it is cheaper. If it’s cheaper, it will win.

If a new technology can do both, automate and augment, its impact on jobs will be highly different along that axis. But in our public conversations, we seem to have lost the capability of maintaining that rather minimal level of nuance (the study authors, to their credit, have not).

I’m once again asking us to not freak out about this wonderful new tech. Use automation to become more efficient. Use augmentation to become even better.

CODA

This is a newsletter with two subscription types. I highly recommend to switch to the paid version. While all content will remain free, all financial support directly funds EPFL AI Center-related activities.

To stay in touch, here are other ways to find me:

Thanks for your clarification. Karen Hao’s Empire of AI shows how big AI firms lean on non-peer reviewed studies to control the narrative. OpenAI’s “right to AI” framing is new and clever, but from a human perspective the real fight is for a right to AI augmentation. When AI automates, entry-level jobs collapse as Stanford study mentions. When AI augments, workers grow. The question isn’t AI or no AI, it’s which kind of AI use we guarantee people access to.

Very insightful Marcel. I think anyone using AI as an augmentation can see that the power of the output is directly dependent on how well the problem statement is formulated and how well the AI is coached. That’s why scientists will not be replaced by AI because all AI can do (for now) is find responses and solutions. But the biggest value of scientists and many other professionals is in being able to formulate hypothesis or framing a problem and probing them.